|

I recently came across Pat Kirkham's book on Furniture Making in London in the Eighteenth Century[i]. There are a number of interesting facts about the firm Ince & Mayhew, many of which were included in her article for the Furniture History Society[ii].

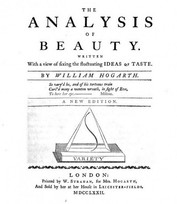

However, one detail that had escaped me up to now was that when John Mayhew married Isabella Stephenson, she had a large dowry. Pat Kirkham writes: John Mayhew’s wife brought a large sum of money to her husband when they married in 1762, and, widowed within the year, Mayhew used approximately three thousand pounds of that money to finance his business. I am going to re-visit the National Archives to see if there is any further information on this, but it did help to explain why Isabella's sister, Ann, William's wife, had no hesitation about taking John Mayhew to court to get a fair settlement on the break-up of the partnership. She would no doubt have known all about that money, and would have regarded it as belonging equally to her family. No wonder she insisted on a more balanced final payment. [i] Kirkham, P. (1988). The London Furniture Trade 1700-1870. Furniture History, 24, I-219. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23406689 [ii] Kirkham, P.. (1974). The Partnership of William Ince and John Mayhew 1759—1804. Furniture History, 10, 56–60. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23403407  The first three plates in the Universal System of Household Furniture, the directory published by Ince & Mayhew between 1759 and 1762, contain Ornaments for Practice and include instructions for novice designers on how to draw. The first plate includes the following description: Plate I – containing several pieces of Foliage properly adapted to young beginners in their first practice of Drawing, being extremely necessary to bring the Hand into that Freedom required in all kind of Ornament, useful to Carvers, Cabinet-Makers, Chasers, Engravers, etc, etc. …. The next plate is called A Sistimatical Order of Raffle Leaf from the Line of Beauty and is described as a compleat Leaf of Foliage; the principal Sweep or Centre Line is that Foundation and Basis of the whole Order of Ornament; that must be first drawn and made perfect (which can only be done by freedom of Hand) before you proceed any further; It was interesting to learn from an article in the RIHA Journal[i], that William Hogarth was promoting the theory of the line of beauty in his book Analysis of Beauty which was published in 1753. He saw the line of beauty as an S-shape, or an inverted S-shape, which he considered conveyed liveliness and activity, which would excite the viewer. This was in contrast to straight lines, which were seen as inanimate. It is interesting to see William Ince used the phrase Line of Beauty and it would seem likely that Hogarth’s book was important to him when learning his trade. His apprenticeship with John West started in 1753, so the book would have just been available. Incidentally a raffle leaf was an architectural ornament. The Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture’s definition is: Serrated, indented, or crumpled leaf-like enrichment with waving indented frond-like (or raffled) edges. Raffling is applied to the notched edges of carved foliage in architectural ornament. I have also discovered that the Universal System of Household Furniture was not known to have been advertised in America until 1766. An advertisement appeared in the South-Carolina & American General Gazette (Charleston) on July 18, 1766. It read: “Robert Wells, At the Great Stationary and Book Shop on the Bay, has imported for sale Chippendale’s and Ince and Mayhew’s designs of household furniture from London.” The advertisement appeared again in 1772.[ii] [i] Anne Puetz, Drawing from Fancy: The Intersection of Art and Design in Mid-Eighteenth-Century London RIHA Journal [ii] Morrison H. Heckscher, English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/48/American-Furniture-1994/English-Furniture-Pattern-Books-in-Eighteenth-Century-America (Dixon, p.68, no.19).  Further to last week’s post, I had a look in the British Newspaper Archives for Ince & Mayhew and then searched again for Mayhew and Ince. The results supported my findings. The firm was called Ince & Mayhew, apart from the eighteenth century articles and advertisements which came out when the firm was still in existence, which referred to Mayhew and Ince. Any furniture for sale at auction stated Ince & Mayhew. Interestingly in the 1870s and 1880s there were a series of advertisements in many local papers looking for copies of furniture directories. They all read the same: OLD BOOKS WANTED on Cabinet Making by Hepplewhite, Ince and Mayhew, or Chippendale. Will give £2 2s for either….. The amount offered was sometimes £2 10s.The address given for replies was 41 Porchester Road, London, later Evering Road, Stoke Newington. In 1878 the advertisement appeared in the following papers: Bristol Mercury, Liverpool Mercury, Worcester Journal, Sheffield Independent, York Herald, Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, Leeds Times, Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, Hampshire Advertiser, Belfast Telegraph. In 1879 it was in the Liverpool Mercury, in 1880 the Glasgow Herald and in 1881 the Gloucester Citizen, Bury Free Press, Leeds Times, Banbury Advertising and the Lancaster Gazette. On 12th May 1894 the Birmingham Daily Post ran a report on an Important Sale of Books at Sothebys at which The Universal System of Household Furniture consisting of 300 designs and 95 plates by Ince and Mayhew had been sold for £25[i], proving a very good investment for the collector. As reported last week, the 1762 edition of the Universal System was specially scarce and a copy in perfect condition was priced by Batsfords in 1940 at £150[ii]. In 1996,Christie’s sold a copy of an intermediate issue, dated about 1765, for £6,325 and in 2011 they sold a copy for £8,125. A first edition, dated 1760, was sold by Bonhams in 2013 for 6500 USD (£4,973 ) and a copy was sold by them from the library of the late Hugh Selbourne, M.D. in 2015 for £6,875 including premium. What has astonished me though is a copy of the Universal System being sold by Potterton Books of York, London and New York for £18,000. This version is printed on twentieth century mottled calf, has gilt decorative borders and red morocco lettering pieces. It is described as a Handsome book. William Ince invented and drew 75 of the 95 plates as well as the title page and I’ve been looking at some of them in my Dover Publications edition. Items such as the library steps and the Ladies’ Dressing Table are really delightful! [i] According to the National Archives Currency Converter, £25 in 1890 would be worth close on £1500 in 2005. £2 2s would be roughly £100. [ii] Davis, Frank, The World of Art in Wartime, Furniture “Convenient to the Nobility and Gentry The Illustrated London News on 25th May 1940. Unsurprisingly the descendants of William Ince are convinced that the firm should be referred to as Ince & Mayhew. After all, William was the talented cabinet-maker who produced the majority of the drawings for their directory The Universal System of Household Furniture. He was the man to whom Matthew Boulton offered a well-aired Bed, wholesome Bread & Cheese and a hearty wellcome[i]. He would have overseen the production of the furniture, probably choosing the workmen, training the apprentices and checking on their output. He was the man who wrote to Lord Myddleton at Chirk Castle to check the paintings on the ceiling to make sure the compartments over the Glass’s in the piers might be correspondant with them[ii]. It is not going too far to say that William Ince was responsible for the furniture produced by the firm.

Why then is it often referred to as Mayhew and Ince? Eighteenth century records almost always refer to the firm as Mayhew and Ince. In their 1759 Agreement John Mayhew’s name comes before William Ince’s on the legal document. Mayhew and Ince is how it is written in the Land Tax returns for the houses they owned and rented; it is referred to as Mayhew & Ince in some directories and advertisements. Charles Ince, William’s son, refers to the Firm of Mayhew, Ince and Sons in his advertisement in the London Gazette of 12th April 1800 where he says he is taking over the firm. Also many of the accounts sent to their clients were headed Mayhew & Ince. However, occasionally they advertised as Ince & Mayhew, such as in an advertisement for a Lease which appeared in The Times on 23rd May 1799 and sometimes in the Bank books for their clients the name of William Ince appears, or Ince & Mayhew, Ince & Co, Messrs Ince. It is also interesting to note how the name has been presented in the antiques world. Initially, their directory was the main focus of articles and as William Ince’s name appears before that of John Mayhew, the firm is referred to as Ince & Mayhew. In 1904 R. S. Clouston wrote an article called Minor English Furniture Makers of the Eighteenth Century Article III-Ince and Mayhew[iii]. An item in The Times dated 8th June 1921 refers to some chairs for which there is reason to think that they are the work of Ince and Mayhew as they resemble an illustration of a chair in the Universal System. An article written by Lieut-Colonel E. F. Strange, Late Keeper in the Victoria and Albert Museum, for The Illustrated London News in 1929 entitled English Hanging Mirrors also referred to the publication of Ince and Mayhew-The Universal System… and had a reproduction of Plate LXXVIII from their Directory. This showed two designs for Oval Glass-Frames and is a delightful illustration by William Ince, with a hunter and dog, birds, squirrels and possibly a little lamb included in the carving. Another article appeared in The Illustrated London News on 25th May 1940. This was entitled The World of Art in Wartime, Furniture “Convenient to the Nobility and Gentry.” by Frank Davis. He included four illustrations from The Universal System, each time referring to the firm as Ince & Mayhew. The particular volume from which they were taken, the 1762 edition, was specially scarce and in perfect condition so was priced by Batsfords at £150; Chippendale’s Director being priced at £25. In 1946 the furniture shop Heal’s ran a series of advertisements using quotations from The Universal System, citing the firm as Ince & Mayhew. In The Times in 1963 Edward Pinto, in an article about the Furniture Makers’ Guild, wrote Such great names in the eighteenth century as Thomas Chippendale, William Vile, Ince and Mayhew were proud to call themselves Upholders first and Cabinet-Makers second. Pinto used the same name for the firm when writing about the Kimbolton Cabinet in another article for The Times in 1969. Lindsay Boynton’s article in 1966 was called An Ince and Mayhew Correspondence[iv]. Colin Streeter consistently refers to Ince and Mayhew in his 1971 article Marquetry Furniture by a Brilliant London Master[v] as does Morrisson Heckscher in 1974[vi]. In 1981 Hugh Roberts wrote articles about Broadlands, called The Ince and Mayhew Connection[vii]. However in the 1990s the name changes to Mayhew and Ince as seen in articles by Hugh Roberts and Charles Cator, in Lucy Wood’s Catalogue of Commodes, and almost always in Lot Notes produced by the auction houses. Does anyone know why? It is very pleasing to note that in his more recent articles Hugh Roberts has started using Ince and Mayhew again[viii]. [i] Boynton, L. (1966). An Ince and Mayhew Correspondence Furniture History, 2, 23–36 [ii] Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales E5126-E5128 [iii] The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 6(19), 47–52 [iv] Boynton, L. (1966). An Ince and Mayhew Correspondence Furniture History, 2, 23–36 [v] Colin Streeter, June 1971 Marquetry Furniture by a Brilliant London Master The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 29 (10), 418–429 [vi] Heckscher, M. (1974). Ince and Mayhew: Bibliographical Notes from New York Furniture History, 10, 61–67. [vii] Hugh Roberts, ‘The Ince and Mayhew Connection, Furniture at Broadlands, Hampshire’, Country Life, 29 January 1981 pp288-90. [viii] Hugh Roberts, 'Precise and Exact in the Minutest Things of Taste and Decoration' : The Earl of Kerry's Patronage of Ince & Mayhew (2013) Furniture History 2013

|

Author

Sarah Ingle is the great great great great grand-daughter of William Ince and has been researching her family history for a number of years. She thoroughly enjoyed the detective work involved in tracing William’s lineage. Archives

December 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed